The Marine Blue

Leptotes marina, the Marine Blue, is a petite, gossamer-winged butterfly whose territory includes southern California. As with many butterfly species, L. marina’s random and unpredictable flight trajectory is an example of an evolved strategy intended to confound predators. A butterfly will encounter many mortal challenges during its lifespan. Most do not make it to adulthood. In addition to predators, long-term climate and short-term weather variables impact the timing, availability and abundance of host and nectar plants in the butterfly’s habitat.

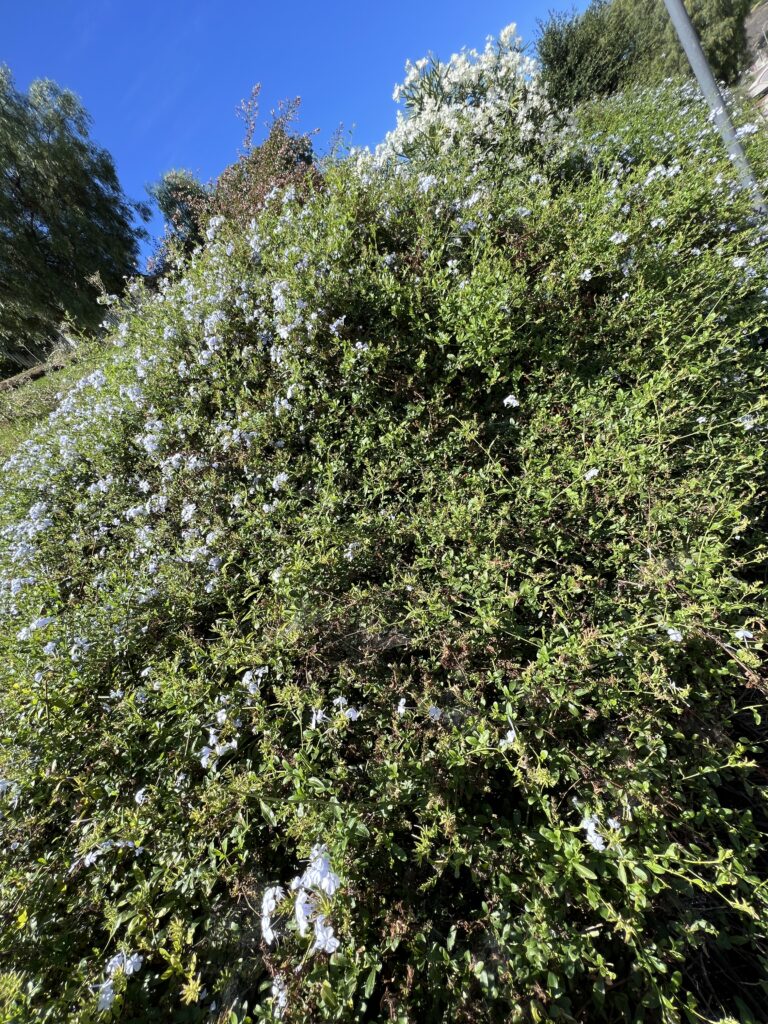

Butterflies spend their brief lives evading predators, feeding and searching for mates. In addition to all that, females, like the one depicted in this photo, are hardwired to seek out host plants on which to oviposit the next generation.

L. marina is an adaptable butterfly. The larvae can feed on a variety of plants associated with the California coastal sage and chaparral ecoregion. Many of these plants are members of the Fabaceae (legumes) family, including species of lupine and milkvetch (both native and invasive) that bloom in the Santa Monica Mountains in spring and early summer. Deerweed, for example, is just one thread among the many that branch out from the taxon Fabaceae. Deerweed is abundant not only in the Santa Monica Mountains and adjacent areas of undeveloped open space but can be found in similar habitats throughout much of California.

Deerweed is usually not present in residential gardens, developed park space, or growing on slopes that overlook surface streets. I have seen it pulled or mowed down in small parks near my house. I think what happens in these cases is that people just do not know that it is a desirable plant to have in a park, even if it produces only tiny flowers. Several butterfly species use it as a host plant, additional butterfly species feed on its nectar. Native bees, including the endangered Crotch’s Bumble Bee, collect nectar and pollen from the flowers. In fact, Deerweed’s tiny flowers, leaves and nitrogen-fixing roots make it a critical habitat plant.

Where the roads, fences, concrete and pavers begin, the landscape of exotics reigns. Only the generalist arthropods, or those most resilient in their ability to adapt, are present in a non-native, curated landscape.

L. marina is one of the resilient ones. It has found a way to expand its territory into suburban southern California, where native host plants are scarce, by recruiting an exotic to play a critical role in its lifecycle.

Sometimes a transcontinental import can do more than sport pretty, blue flowers while preventing erosion on a steep slope.

Blue Plumbago’s Journey

The native range of Blue Plumbago, Plumbago auriculata is South Africa. In 1652, the Dutch East India Trading Company established the Cape Colony settlement. The settlement was located at the at The Cape of Good Hope, the southernmost tip of the African continent. The settlement was a resupply and layover stop for trade ships traveling between present day Jakarta and the Netherlands. The East India Trading Company became the de facto government of the Cape Colony. The Company’s rule over its subjects was an authoritarian one.

The detailed history of the region that is now the Republic of South Africa is a familiar one in human history, mired by the atrocities that accompany all imperialist projects: the quest for power, land and other resources. I will relay the broad strokes only, since how P. auriculata came to California is my subject here.

Ships of men arrived from the Netherlands and later from Britain looking for treasure and resources that they could extract, trade and sell. The indigenous peoples were displaced, their lands were taken, their bodies subjected to imported diseases like smallpox, as well as to the worst potentialities of the human animal’s nature: enslavement, war and genocide. All of this went on for hundreds of years, in various permutations.

During this period, probably earlier rather than later, P. auriculata found its way to new ecoregions in Europe and beyond. Eventually it got a lift westward, across the Atlantic to the Americas. Today on the North American continent, robust populations of P. auriculata are concentrated in Florida, California, Mexico and throughout Central America.

Blue Plumbago and the Marine Blue

In 1990, the researcher John J. Brown published Urban Biology of Leptotes marina, a research paper in which he described his observations and analysis of the species’ ability to use P. auriculata, as a host plant. While the technical details are beyond my expertise to decipher much less explain, the bottom line is that the chemistry of the plumbago shrub provides the L. marina larva with the right mix of nutrients that it requires to progress from egg to adult butterfly. P. auriculata is not a member of the legume family. In fact, until our species decided to plant it near or within the Marine Blue’s range, the two species might as well have inhabited parallel universes.

Leptotes marina is one of few native North American butterflies that has benefited from the activities of man by its remarkable switch to a new larval host introduced from South Africa and to a nectar source and an ant introduced from South America, none of which are closely related to the butterfly’s native resources. This flexibility undoubtedly has led to an expansion in range, at least ecologically and temporally, over the past 60 years, resulting in the butterfly’s invasion and successful colonization of urban environments.

Brown, John. (1990). Urban biology of Leptotes marina (Reakirt) (Lycaenidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society. 44. 200-201.

The nectar source that Brown alludes to is Schinus terebinthifolia, the Brazilian Peppertree, an exotic species from South America. Brown observed L. marina adults visiting this tree to feed on the nectar produced by its flowers.

The California Invasive Plant Council notes that S. terebinthifolia is not yet a widespread problem in the state. As a homeowner with a neighbor who stubbornly maintains an ever-expanding stand of the invasive and in my opinion, noxious species just on the other side of my property boundary, I would say, “Well that depends on the situation.” S. terebinthifolia spreads aggressively through underground roots; I have quite a few in my backyard. The roots produce a growth inhibitor that affects the healthy growth of other plants and shrubs. The only way to eliminate the tree is to use a very strong herbicide or remove all the growth from the roots up. I am engaged in a long-term diplomatic effort to accomplish the total removal option, at my own expense. So far, the only diplomatic communication has come from my side.

The ant that Brown mentions is Linepithema humile, the Argentine Ant. L. humile’s native range is in parts of South America associated with the Parana River drainage. While it does not appear to be a major problem within its native range, the ant now exists of all continents except Antartica, and it has become one of the worst invasive pests on the planet.

L. humile farms and protects insects that produce a sweet waste product known as honeydew. Aphids are frequently associated with L. humile. If you notice an aphid infestation on a plant or shrub located in a maintained landscape, you will usually see many L. humile individuals patrolling the plant as well. What are they doing? They are gathering food. L. humile workers collect honeydew and bring it back to the nest to feed the queens and larvae.

Like aphids, L. marina larvae excrete honeydew. Brown noted that each larva observed on the P. auriculata bushes in the study area was tended by several L. humile ants.

Incidentally, within P. auriculata’s native range of South Africa, there are at least two Leptotes species that use the shrub as a host plant, the Short-toothed Blue, Leptotes brevidentata and Common Blue, Leptotes pirihous. If one considers that the larvae of these two butterfly species share with L. marina a specific chemistry requirement in host plants, it is not unreasonable to hypothesize that they share a common ancient ancestor, from a time before the continents drifted away from each other.

Brown’s study found that the L. marina caterpillar finds the nutrients it requires by feeding specifically upon the reproductive parts of P. auriculata’s developing flower buds, rather than the plant’s leaves.

The clusters of P. auriculata shrubs that contributed to my motivation to write this essay are located on a steep slope that overlooks a busy suburban road called Sunset Hills Boulevard, in Thousand Oaks, CA, just off the 23 freeway. Because of its proximity to the freeway, the location is polluted with noise. Six lanes of traffic hurtle non-stop, north and south beneath an overpass located just a hundred yards or so below the location where I found the shrubs. The spot was also near the entrance and exit ramps to the freeway. The sounds of rapid acceleration along Sunset Hills Boulevard added frequent exclamation points to the continuous highway roar.

I noticed a cloud of butterflies around the shrubs. They drew me in. Butterflies, or course, do not know or care about noise.

Then I entered the small habitat, drawn by the butterflies that had the effect of commanding all my attention. I was a version of Alice falling, not down a rabbit hole, but certainly into another world. The noise of internal combustion engines and rapid acceleration receded, farther and farther from my hearing, so far away that it became possible that the noise never existed at all. I was in the branches, in the forest, a visitor from a wasteland who had found an escape portal in a most unlikely location. I entered and willed the hatch to close behind me. The sounds of so many people gnashing their teeth and howling at each other winked out. Here was a sanctuary, so unexpected in this of all places. My mind opened; it anchored itself on the fleeting configurations of small creatures living their lives as they must, wherever they might. They gave me a sense of humility, purpose, and hope. In that world, nature had found a way once again.

Native plants would have been a better choice on the slope. Manzanita, toyon, ceanothus, sugar bush, lemonade berry are just a few of the shrubs that have perfected their alignment with the climate and the soil over thousands of years. Any one of them would be better than P. auriculata at maintaining the balance in the habitat by providing resources for the insects and animals that co-evolved with them. But none of them would be a suitable host for L. marina’s larvae.

P. auriculata might not be the ideal choice, but it is not invasive in California. It has the fortuitous attribute of being able to host L. marina larvae, and it is a nectar source for the White-lined Sphinx moth. Other butterfly and moth visitors seeking nectar are likely. Some of the winged arthropods that visit the shrub become food for the Western Spotted Orb Weaver and Green Lynx spiders and other beneficial predators.

My final take on P. auriculata is an aphorism attributed to the French satirist Voltaire: Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good.